In the integrated workflow of modern steelmaking, the ladle is far more than a simple refractory-lined vessel. It is a metallurgical reactor, a transfer vehicle, a thermal reservoir, and a pivotal interface between primary steelmaking units and downstream casting operations. The performance of a steel plant—its productivity, its metallurgical precision, and its operational stability—is deeply linked to how effectively its ladles are engineered, maintained, and operated.

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the ladle within a steel plant, including its structural configuration, refractory system, auxiliary equipment, metallurgical functions, and the technological evolution that continues to enhance its capabilities.

1. Overview of the Steelmaking Ladle

A steelmaking ladle is a cylindrical, high-capacity vessel used to receive, transport, refine, and deliver molten steel. Depending on the plant configuration, capacities range from 30 tons in specialty shops to 350 tons in large integrated mills. While its primary function is transporting hot metal from furnaces (BOF, EAF) to continuous casting machines (CCM), its role has expanded significantly over the last several decades due to the increased emphasis on secondary metallurgy.

In modern steel plants, the ladle is central to a suite of operations including:

- Alloy addition and compositional adjustment

- Desulfurization and deoxidation

- Temperature homogenization

- Inclusion removal and cleanliness enhancement

- Vacuum degassing (VD/VOD) when applicable

- Argon stirring for refining and homogenization

Thus, the ladle is effectively a controlled metallurgical environment.

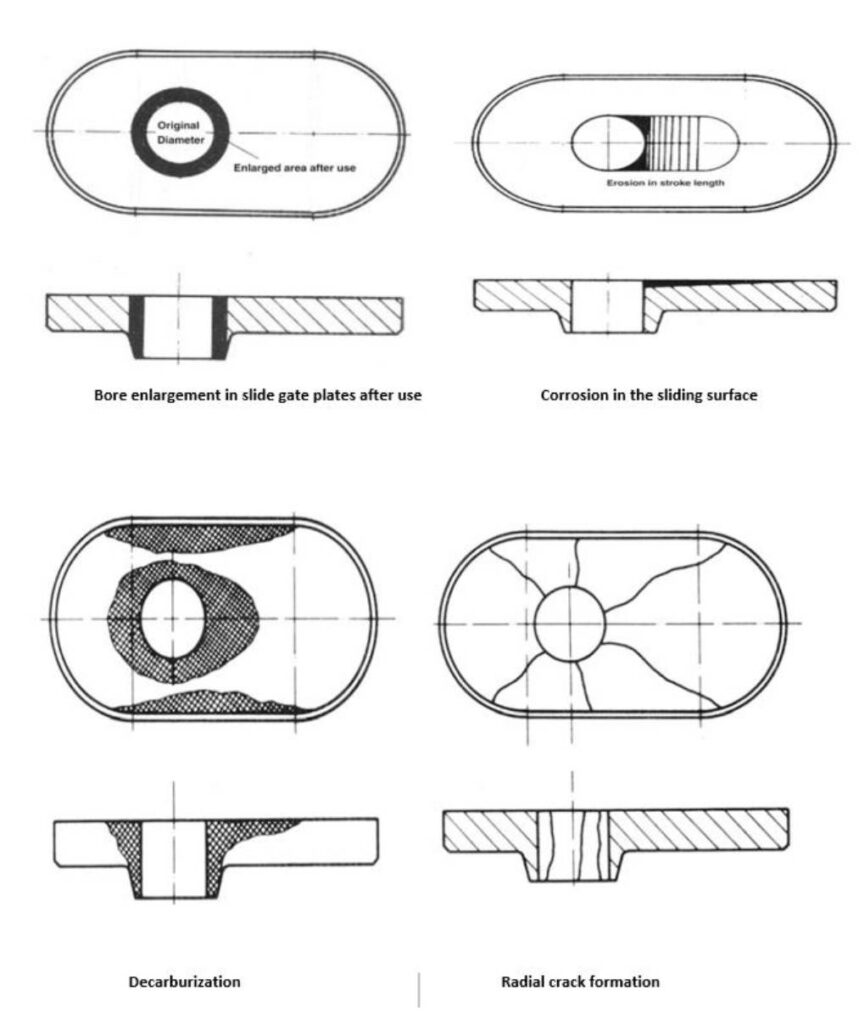

2. Structural Design of the Ladle

A ladle’s structural integrity must withstand extreme thermal and mechanical stresses. Its core components include:

2.1 Steel Shell

The outer shell is fabricated from thick, high-strength steel plate, often with reinforcing rib structures. The shell must resist deformation under the static load of molten steel—at temperatures exceeding 1600°C—and the dynamic stresses introduced during handling, lifting, tilting, and thermal cycling.

2.2 Trunnions and Yoke

Trunnions are heavy forged steel pins welded or cast into the ladle shell to allow the vessel to sit securely in a ladle turret or crane hook. The yoke assembly distributes lifting forces uniformly. Ladle turning mechanisms, especially in BOF shops, rely on robust trunnions to enable controlled tilting for tapping and slag removal.

2.3 Refractory Lining

The refractory lining protects the steel shell, ensures insulation, and maintains steel quality. The lining typically comprises:

- Working lining: High-grade magnesia-carbon brick (MgO-C) or dolomite brick, resistant to slag corrosion.

- Safety lining: A secondary thermal barrier beneath the working lining to protect the shell in case of localized wear.

- Bottom castable: Often a high-alumina or MgO castable that stabilizes the vessel floor, integrates well with bottom plugs/nozzles, and provides erosion resistance.

Modern linings are engineered to withstand severe slag attack, thermal shock, and chemical reactions while maximizing ladle campaign life.

3. Metallurgical Features of the Ladle

3.1 Bottom Purging System

Most steelmaking ladles incorporate porous plugs or tuyeres embedded in the bottom lining. These allow controlled argon injection, which provides:

- Metal bath stirring

- Homogenization of temperature and chemistry

- Inclusion flotation and removal

- Improved desulfurization kinetics

Bottom stirring is indispensable for high-quality steels where steel cleanliness and precise chemistry control are required.

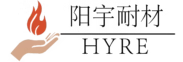

3.2 Ladle Slide Gate System

The slide gate controls the flow of molten steel during casting. Key characteristics include:

- Three-plate or two-plate design

- High-purity alumina-carbon plates

- Hydraulic actuation for fine flow control

This system ensures stable casting rates and prevents nozzle clogging.

3.3 Shroud and Nozzle System

During casting, a ladle shroud connects the ladle outlet to the tundish to minimize reoxidation. Nozzle geometry, refractory quality, and flow dynamics directly influence steel cleanliness.

4. The Ladle in Secondary Metallurgy

The transition from simple steel transfer to secondary metallurgy has transformed how ladles are designed and operated. Key ladle-based secondary processes include:

4.1 Ladle Furnace (LF) Treatment

The ladle furnace refines steel through:

- Electrical arc heating

- Argon stirring

- Alloy and flux addition

- Slag refining

This unit allows precise adjustment of carbon, sulfur, phosphorus, temperature, and composition.

4.2 Vacuum Degassing (VD/VOD)

When fitted with vacuum seals and lifting equipment, the ladle serves as the reaction chamber for degassing. Benefits include:

- Removal of hydrogen and nitrogen

- Deep decarburization (VOD for stainless steels)

- Inclusion floatation enhancement

- Improved steel cleanliness for demanding applications (automotive, aerospace)

4.3 Ladle Desulfurization

Ladle refining slags—high in CaO and MgO—interact with molten steel to reduce sulfur content. Stirring accelerates the reaction. This step is vital in producing line-pipe steels, bearing steels, and other low-sulfur grades.

5. Refractory Engineering and Campaign Management

Refractory design has a major influence on ladle performance and cost efficiency.

5.1 Wear Mechanisms

Typical ladle wear occurs due to:

- Chemical corrosion from slag attack

- Thermal shock during tapping

- Erosion from argon stirring

- Mechanical impact from scrap and alloy additions

5.2 Extending Ladle Life

Plants employ techniques such as:

- Slag optimization (basicity, viscosity, FeO content)

- Slag splash coating after tapping

- Controlled heating and cooling cycles

- Automated ladle condition monitoring

A well-optimized ladle campaign can exceed 100 heats, depending on steel grade and operational severity.

6. Automation and Digitalization in Ladle Operations

Advanced steel plants increasingly incorporate digital tools to optimize ladle performance.

6.1 Ladle Tracking and Scheduling

Real-time ladle management systems monitor:

- Ladle location

- Temperature loss profiles

- Remaining lining life

- Upcoming heat assignments

This supports thermal and logistics optimization, reducing delays and unnecessary reheating.

6.2 Thermal Modeling

Thermal prediction algorithms help determine:

- Heat compensation needed at the LF

- Optimal preheat time

- Temperature drop during transfers

This ensures the steel enters the caster at the correct temperature window.

6.3 Wear Prediction Models

Refractory wear sensors and AI-driven models forecast failure risks, allowing proactive maintenance and minimizing production interruptions.

7. Ladle Preheaters and Temperature Control

High-temperature refractory linings demand controlled preheating cycles. Ladle preheaters:

- Use oxy-fuel or natural-gas burners

- Raise lining temperature to 1000–1200°C

- Reduce thermal shock during tapping

- Minimize steel temperature loss during handling

Modern plants integrate automated burner control with ladle scheduling systems to guarantee consistent thermal conditions.

8. Operational Best Practices

Effective ladle operation is essential for safety and steel quality.

8.1 Slag Control

Maintaining low iron oxide (FeO) in slag reduces refractory wear and sulfur reversion. Operators regulate slag foaming, viscosity, and flux additions.

8.2 Stirring Optimization

Stirring must balance refining kinetics with wear control:

- Excessive stirring erodes the lining

- Insufficient stirring reduces homogenization efficiency

Flowrate curves and pressure feedback systems are used to maintain optimal conditions.

8.3 Flow Control Reliability

Regular inspection of slide-gate plates, nozzles, and shrouds is mandatory to prevent casting disruptions.

9. Safety Considerations

Ladle operations involve extreme temperatures and kinetic hazards. Key safety measures include:

- Rigorous maintenance of trunnions, bails, and yokes

- Monitoring shell deformation and crack formation

- Ensuring refractory integrity before each campaign

- Maintaining strict protocols for vacuum lifting and emergency tapping

Failures are catastrophic; therefore, predictive maintenance and real-time monitoring are crucial.

10. Conclusion

The ladle is a critical metallurgical reactor and logistical node within any steel plant. Its design, maintenance, and operation influence steel quality, energy efficiency, process stability, and plant safety. The field continues to evolve with advancements in refractory technology, bottom-stirring systems, automated ladle tracking, predictive wear analytics, and integrated secondary-metallurgy systems.

A well-engineered ladle allows steelmakers to meet increasingly stringent requirements for composition, cleanliness, and casting performance. As steel production becomes more technologically sophisticated, the ladle will remain an indispensable component—both robust in physical structure and refined in its metallurgical capabilities—at the heart of modern steelmaking operations.