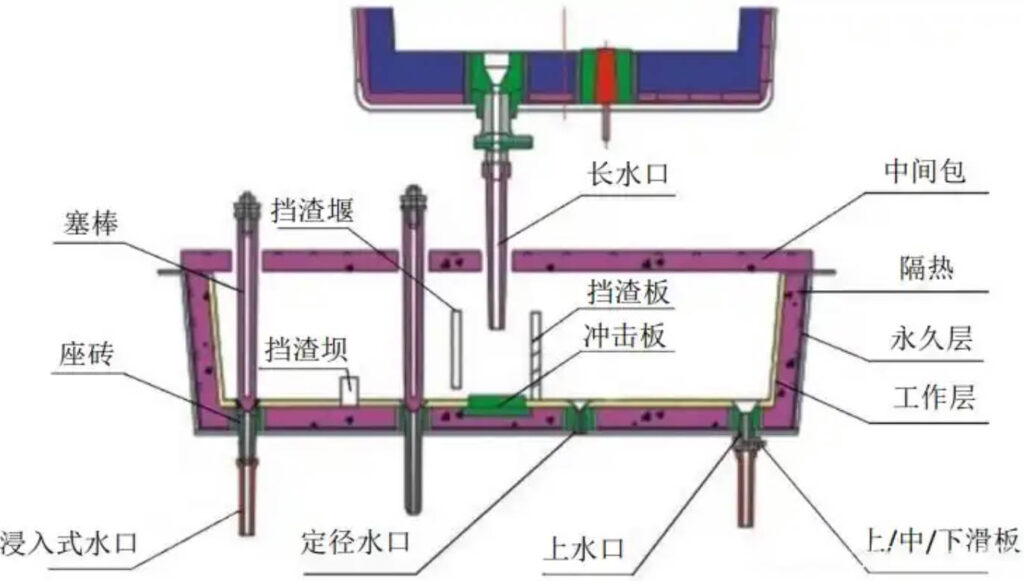

Liquid steel emerging from the ladle is extremely reactive: if it contacts air before entering the tundish, free oxygen and nitrogen dissolve rapidly, oxidizing Al/Ti deoxidizers and forming large alumina or nitride inclusions. Since oxygen reacts much faster than nitrogen, steelmakers often track nitrogen pickup as a proxy for air entrainment. In practice, tight limits are imposed – for example, a clean-steel caster may require less than ~10 ppm N increase during the ladle–tundish transfer. To achieve this, multiple protection strategies are used in combination. In summary, common measures include:

- Inert-gas stream shielding: injecting argon around the steel jet to displace air.

- Tight gating and seals: using stopper-rod or slide-gate valves with ceramic/metal gaskets to prevent air leaks.

- Synthetic ladle slag cover: maintaining a fluid synthetic flux on the ladle to scavenge oxygen and inclusions.

- Tundish covers and purging: blanketing the tundish with refractory lids or powders (often with argon purge) to maintain an oxygen-free atmosphere.

- Gas stirring: bubbling inert gas (argon) through ladle/tundish plugs or the sliding gate to float inclusions and homogenize the steel.

Each of these is explained below, with examples from industrial practice and recent research. Together they form a “defense-in-depth” that minimizes oxidation and inclusion formation during the ladle-to-tundish transfer.

Argon Shrouding and Stream Protection

Ladle shrouds and argon curtains physically isolate the steel stream from air. The ladle’s slide gate or stopper aligns with a refractory ladle shroud (tube) through which the steel flows, and argon is injected around the shroud neck or tip to blanket the jet. The shroud was originally developed precisely for this purpose: to “shield the teeming stream from atmospheric contamination”. Early trials showed dramatic results – for instance a ladle shroud trial at Burns Harbor found the downstream steel oxygen level fell by roughly half. Modern shrouds (typically alumina or alumina–graphite) last dozens of heats and, when combined with argon, achieve very low oxygen pickup.

Argon injection plays a key role. In a typical setup, an argon lance or port is placed at the ladle shroud head so that gas enters and envelops the steel column. The argon creates a protective inert curtain around the stream, pushing out air and preventing turbulent air entrainment at start-up. Continuous‐casting practice often uses multiple barriers at once: for example, argon gas may be injected through the shroud neck while an external “curtain” of argon flows from gas jets around the shroud shoulder, and a deformable gasket seals the shroud-to-nozzle joint. This combination of mechanical shrouding and gas shielding is highly effective. Even when the shroud is opened submerged (below the bath surface), the argon atmosphere and seal prevent ambient air from folding into the stream. As one review notes, modern shrouding is “optimized to minimize air ingress by using argon injection and proper sealing/holding technologies”.

Another innovation is the immersed-opening shroud, which extends the shroud exit farther downward so that the ladle gate opens while the steel side is still submerged. In this way the steel jet is never exposed to air. RHI Magnesita reports that such bell- or reverse-taper shrouds (see photo above) “ensure avoiding reoxidation of the steel stream” during ladle opening. These deeper, larger-diameter shrouds typically allow a cold ladle to pour without a gap (and even reduce slag-powder splash), albeit at the cost of more refractory mass and argon requirement.

In sum, argon shrouding – via both physical tubes and inert gas curtains – is the first line of defense. Properly implemented, it can cut oxygen pickup dramatically and prevent aluminum or calcium in the steel from oxidizing on contact with air.

Ladle and Tundish Sealing Techniques

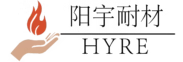

Along with shrouding, minimizing any leak path is crucial. The ladle-to-tundish stream typically passes through a flow control device (either a sliding gate or a stopper-rod valve) at the ladle bottom. All joints and penetrations are potential air inlets and must be sealed or purged. For instance, sliding gate systems insert a ceramic or metal valve plate in the flow; special gaskets (often deformable and sometimes metal-reinforced) are used around the gate edges to make the joint gas-tight. Vesuvius notes that “metal tight gaskets” are installed at sliding-gate bores and nozzle interfaces “to minimize the risk of air ingression”.

Slide-gate connections: In a slide-gate caster, the lower nozzle of the ladle (attached to the shroud) fits into the tundish adapter. Here a gasket or compliant seal (metal or ceramic) is critical. Industry literature describes multi-layer soft or ceramic gasketing at the nozzle-to-shroud joint, often made so that it compresses and prevents any air gap. In practice, argon is often provided under positive pressure to these joints as well, further ensuring no back-flow of air. (In fact, some patented designs deliberately inject a small argon flow around the slide-gate bore to maintain a “gas seal” if the mechanical fit is imperfect.) The combination of physical seal and purge gas can reduce macro-inclusions and gas pick-up: one study reported that argon purging of the slide-gate housing cut 50–100 μm oxide inclusions from about 3 to 0.6 per cm², and 100–200 μm inclusions from 1.4 to 0.4 per cm².

Stopper-rod systems: Caster stoppered systems use a ceramic stopper rod inserted into the ladle shroud to meter flow. These must also be sealed in the tundish lid, and often have a purge line. Injecting argon up through the hollow stopper or around its flange is a common practice. Industrial data show that argon-lancing the stopper can greatly cut atmospheric uptake. For example, experiments found that blowing argon through the stopper assembly reduced ladle-to-tundish nitrogen pickup from ~5 ppm to 1.8 ppm, and total oxygen in the cast slab from 31 ppm to 22 ppm. This kind of purging also dispersed the size of alumina clusters and reduced clogging.

Shroud-to-nozzle seals: At the very interface between ladle shroud and tundish nozzle, rigid support plates or mats are often used to seal the gap. The quoted RHI Magnesita bulletin even emphasizes that “sealing must be regarded as the first priority and shielding as the second” at the shroud connection. In other words, finding a leak-proof mechanical joint (e.g. with metal-reinforced blocks or expanded gaskets) is more important than simply blowing more gas. If any small leak persists, an argon curtain or gasket is placed there: combined solutions (soft gasket + argon curtain + precise machinery alignment) are commonly employed to make the stream essentially hermetic.

To summarize, robust sealing around slide gates, nozzles and stopper rods – often augmented by a modest gas purge – is another key element. Properly designed, these techniques prevent air from “sneaking” into the steel path, and complement the argon shroud above.

Synthetic Ladle Slag and Steel Protection

After tapping from the furnace, steel is typically refined in the ladle (with alloys, deoxidizers, and so on). A synthetic refining slag is then held on top of the molten steel as a protective cover. These synthetic slags (usually Ca–Al or Ca–Mg–Al aluminate formulations) serve several functions simultaneously:

- They form a physically insulating cover on the steel surface, reducing heat loss and limiting steel splashing.

- They are chemically designed to scavenge oxygen. A fresh, basic synthetic slag has a strong affinity for dissolved O and S in the steel; it reacts with any oxygen (or sulfur) that might diffuse out of the steel, thereby preventing re-oxidation of Al, Ti or other deoxidizers in the melt.

- The slag also absorbs non-metallic inclusions. Complex spinel or alumina inclusions in the steel can wet into the slag, trapping them at the interface.

In short, the synthetic ladle slag acts as a sacrificial barrier between liquid steel and air. One industry review explicitly states that the slag “covers liquid steel with an insulating layer” and “removes the possibility of reoxidation from atmospheric oxygen”. In modern practice, the slag is kept fluid by adding flux in the ladle furnace or ladle immediately after tapping. It is held at a moderate height (often 20–50 mm on the steel surface) and continuously skimmed or densified. This slag layer must be balanced (basic enough for desulfurization but not so fluid as to drain away) and is often monitored chemically.

Whenever the slag is disturbed (for example, during pouring or long holds), its protective function diminishes. Therefore plants take care to control slag carryover and maintain the slag blanket. In some systems, secondary (top-flow) argon is even injected through the slag to stir and degas the steel; this can boost its oxygen-scavenging effect. The bottom line is that a robust synthetic slag cover in the ladle significantly reduces the free oxygen available for re-oxidation when the steel is poured out. It should be noted that the effectiveness of this cover depends on its chemistry and thickness, which are often tailored to the steel grade (higher Al steels may use more CaO-rich slag, etc.).

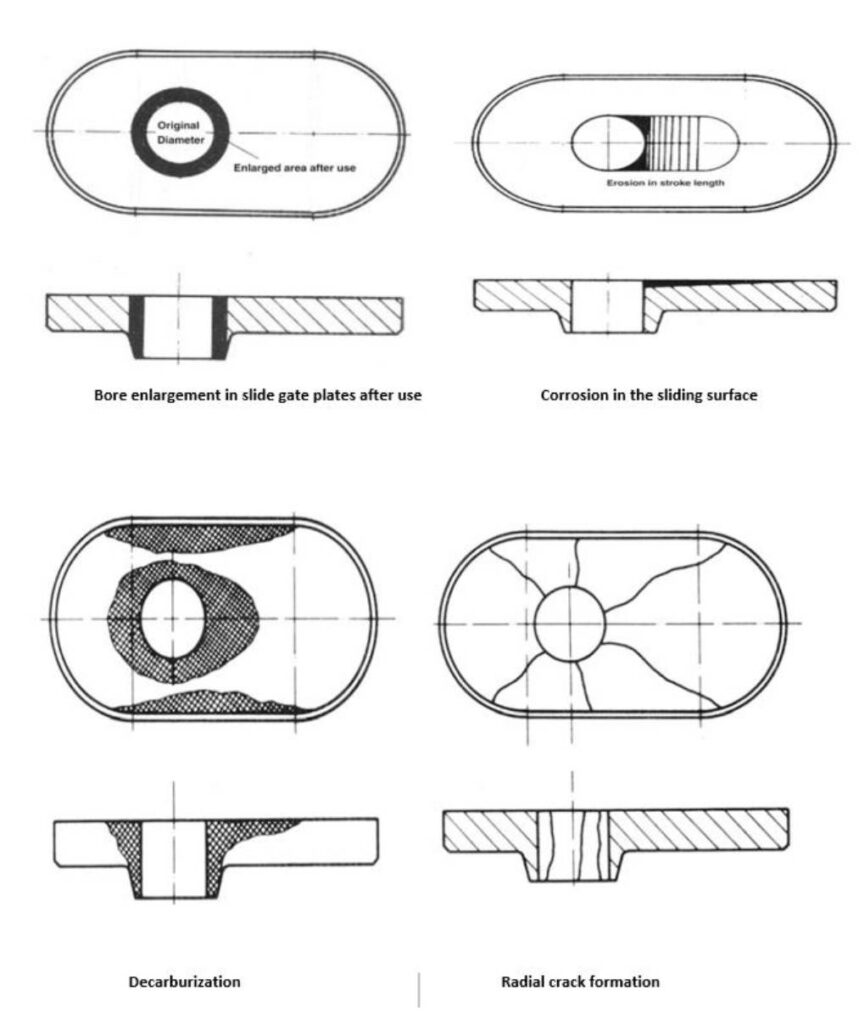

Tundish Covers and Refractory Design

Once the steel passes through the shroud, it enters the tundish – a shallow refractory basin. If the steel surface in the tundish is open to air (often called an “open eye”), re-oxidation can occur at the meniscus or by air entrainment into the flow. Thus modern tundish practice also employs covers and seals on the tundish itself.

A standard solution is a rigid tundish lid (steel plates lined with refractory) with openings only for the ladle shroud(s) and stopper(s). The gap around each nozzle in the cover is precisely filled with a castable seal or ceramic board so that the molten steel is never exposed to ambient air. Often a layer of insulating powder (tundish flux/powder) is used over the steel bath, which quickly melts into a slagbed that further closes any small leaks and desulfurizes the steel.

In many modern casters, the tundish cover is augmented by inert gas purging to maintain a positive pressure. For example, recent research on Argon Blowing through Tundish Cover (ABTC) shows that sealing all lid openings and bubbling argon through dedicated cover pipes can purge out residual air before pouring starts. Numerical and plant trials found that with ~100–200 Nm³/h of argon from the cover, the remaining oxygen fraction in the empty tundish stayed below ~1%. Under these conditions the steel’s nitrogen uptake was cut by ~90% and its loss of aluminum by ~7%, compared to an unprotected tundish. In actual operation, Korean and European mills using cover-argon report far fewer inclusions and surface defects (e.g. one study saw ferritic inclusions drop ~38% and Al–Ti loss plummet when cover purging was used)

In practice, a tundish cover is often fitted with dozens of small argon ports (embedded in the cover lining) and some baking holes for preheating the vessel. Before casting, the cover is baked hot to >1000 K (to drive off moisture), then argon is blown until all air is expelled from the chamber. The remaining steel is poured under this blanket of argon. The combination of a tight refractory lid and slight positive gas pressure effectively “inertizes” the tundish. One patent description summarizing this approach noted: “Molten steel in the ladle is covered with slag, the tundish space with an inert gas to effectively eliminate free oxygen and nitrogen from the tundish prior to and during casting”. In short, any strategy that keeps the tundish atmosphere inert (sealed covers, ceramic mats, or even flexible ceramic “pillows”) will minimize reoxidation.

Tundish refractory design also plays a role: high-alumina, low-silica linings are chosen to avoid reduction reactions (Al in steel can react with SiO₂ or FeO in the lining, forming more alumina). Flow-control refractory such as impact plates, weirs and dams are shaped to reduce surface turbulence and prevent slag entrainment. For example, sloped and asymmetric baffles help create a “quiet” zone away from the inlet jet, so that the steel surface is not violently exposed to air. These tailored refractory designs, together with the sealing lids and covers, complete the air-shielding of the tundish.

Inert Gas Purging and Flow Control

Beyond shielding, inert gas purging is used to internally clean and homogenize the steel. In both the ladle and tundish, porous plugs (gas purging plugs) can inject argon from below. These fine bubbles rise through the steel, providing several benefits: they float nonmetallic inclusions upward into the slag cover, they stir the melt for uniform chemistry and temperature, and they strip out dissolved gases. The approach is so effective that almost all modern ladle furnaces and many tundishes use argon bottom-stirring. As one review summarizes, “the application of argon in ladle stirring… and the argon bubbling curtain in tundish… has provided a great protective effect on removing inclusions”.

In the tundish, inert bubbling can be continuous or intermittent. A curtain or nozzle arrangement across the inflow (often called a bubble curtain or purge curtain) can deflect the incoming steel and stabilize the flow pattern. In many casters, small argon plugs (or linear diffusion plugs) near the ladle nozzle orifice gently break up the jet and capture inclusions. Laboratory and plant studies confirm that even modest argon flow rates significantly clean the steel: one plant reported a 25–80% reduction in large inclusions just by argon-stirring through the stopper rod.

Another purging practice is slide-gate purging, where inert gas is injected through the gate housing itself (some designs have a hollow actuator or injection port around the gate). This saturates the metal with argon right at the pouring location and further displaces air. As noted above, argon flowing through a slide gate’s upper plate nearly eliminated mid-size inclusions in experimental trials. Although pushing too much gas can risk “open-eye” disturbances, controlled purging in the ladle or tundish is generally net-beneficial for cleanliness. Modern control units can regulate these flows precisely; some even measure bubble dynamics to optimize mixing without causing reoxidation.

In summary, inert-gas stirring is a core part of the clean-casting recipe. By coupling gas purging plugs and shrouded pouring, plants achieve deeper mixing and inclusion flotation while still isolating the steel from air.

Inclusion Control and Re-oxidation Avoidance

All of the above practices serve the ultimate goal: prevent inclusions. Inclusions that arise during ladle-to-tundish transfer are almost always oxides or oxy-sulfides formed by reoxidation or slag erosion. For example, alumina clusters can form when Al in liquid steel meets oxygen (from air or slag) and agglomerates. Inclusions originating from air contact tend to be large and irregular. To avoid them, the rule is simple: keep the steel away from O₂. With Argon shrouds, sealed joints, protective slag, covered tundishes and gas purging all acting in concert, the steel sees virtually no fresh oxygen during transfer. Any tiny remaining oxygen in the flow is absorbed by the flux or carried out by argon bubbles.

Effective inclusion control also implies good flow design: the steel stream should enter the tundish in a way that does not disturb the slag. Flow impact pots, multi-layer weirs, and optimized nozzle shapes are all used so that the jet is well-dampened. A laminar, submerged entry with minimal splashing prevents the steel from shearing off slag or air into the flow. Computational and water-model studies are used industrially to refine these features (for instance, “tundish impact pots” are customized to shape the flow for plug-like movement). These measures ensure that inclusions already in the steel have a chance to float out of the liquid.

In practice, eliminating re-oxidation in the transfer step unlocks the value of prior ladle cleaning. If the steel carries oxygen from air, it simply generates new alumina inclusions (as oxygen “strips” Al from the melt). Preventing air ingress means that any dissolved Al remains bound in solution or forms fine, controllable oxides. This strategy of “inclusion engineering” – keeping the liquid steel in a protective, deoxidized state through the transfer – is the hallmark of modern clean casting. The data bear it out: plants report far cleaner steel when shrouds and covers are used. For example, a Scandinavian mill saw its defect rate drop by 38% on IF steel and a Korean mill cut Al-inclusion counts sharply, after adopting cover-argon and enhanced shrouding.

Industry Practices and Innovations

In current steel plants, these anti-oxidation technologies are deployed in concert. Many casters follow internal standards (or industry guidelines) that specify nitrogen limits, argon flows, and material lifetimes. For example, having baked the tundish at 1000 K, operators might blow 100–200 Nm³/h of argon through the cover for 5–10 minutes before tapping, then maintain ~80–100 Nm³/h during casting to keep O₂ at ~1% or less. Ladle shrouds are often handled by robotic manipulators and include cooling lines; shroud materials may have metal ‘cans’ to reinforce the throat and extend life under aggressive pouring conditions. Slide gates are now available with gas-tight enclosures: for example, RHI’s INTERSTOP® SX ladle gate uses a sealed housing that can be purged with inert gas and even incorporates slag-detection (EMLI) to avoid starting the pour with molten slag in the spout.

Quality control protocols routinely monitor nitrogen pickup after the transfer to verify the protection. Targets like <5–10 ppm N from ladle-to-tundish are typical for ultra-clean grades. Metallurgical labs analyze inclusion populations in tapped steels; a successful transfer shows only small, globular remnants of original inclusions rather than chunky re-oxidation defects.

On the research and innovation side, work continues on even finer control. Examples include “hybrid” purging plugs that generate millions of fine bubbles without causing surface scouring, or vibration-sensor systems on gas plugs to infer bubble size distribution in real time. Tundish flow is analyzed by computational fluid dynamics to improve baffle shapes. Some patents describe fully sealed tundish boxes (akin to metallurgical chambers) that run under argon pressure. In short, every aspect of the transfer path – from ladle shroud design to tundish lid mechanics – is continuously refined in the pursuit of zero air ingress.

In conclusion, protecting liquid steel from oxidation during ladle-to-tundish transfer requires an integrated approach. Argon shrouding physically shields the stream, seals and gaskets prevent leaks, synthetic slag acts as a sacrificial cover, tundish lids with purge systems blank out air, and inert gas stirring carries off inclusions. When properly executed, these methods allow the steel to enter the continuous caster virtually as pure as it was when it left the refining furnace. The result is cleaner steel, fewer casting defects, and more reliable caster operation – benefits well documented by both plant experience and metallurgical studies.