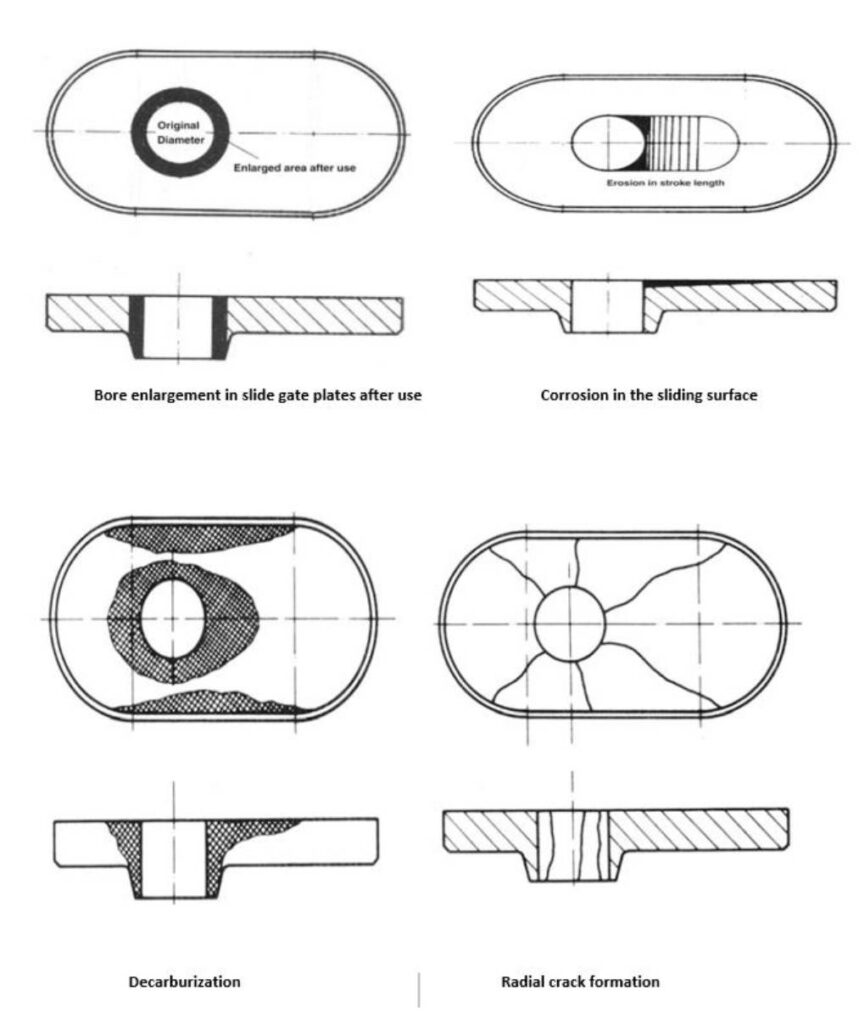

The four main components used in continuous casting refractory materials—submerged entry nozzles, ladle shroud, monoblock stoppers and slide gates, and sizing nozzles—serve to transport molten steel, isolate gases, and control the steel flow. In particular, submerged entry nozzles are used between the tundish and the crystallizer in continuous casting to protect the steel flow, prevent secondary oxidation of the molten steel, promote the flotation of inclusions, prevent the impact of molten steel on the crystallizer surface during open casting, and reduce slag entrapment. A submerged entry nozzle currently in use in production is shown in Figure 1 . Its materials are mainly divided into two categories: fused silica and alumina-carbon. Fused silica is mainly composed of SiO2 , with a SiO2 content ≥ 99% , a room temperature compressive strength of 40 MPa , an apparent porosity ≤ 18% , and a bulk density of about 1.84 g/cm3 . The alumina-carbon body is mainly composed of Al2O3, supplemented by C and SiO2 , with Al2O3 accounting for 35 % and C accounting for 20% . In the slag line area , C accounts for 20% and ZrO2 accounts for 70% . It has a room temperature torsional strength of 23.34 MPa , an apparent porosity ≤ 16% , and a bulk density of about 2.5 g/ cm3 .

During the casting process, nodule formation at the tundish submersible nozzle not only hinders the injection of molten steel into the crystallizer but also affects the flow field of the molten steel within the crystallizer and the flotation of inclusions, thus impacting internal quality; especially when the nodule is washed away and incorporated into the solidified billet. Upon entering the hot rolling process, defects such as inclusions and scales appear on the surface of the strip, severely affecting the surface quality and performance of the hot-rolled strip. This paper, through tracking nodule-forming steel grades and using tools such as scanning electron microscopy, conducts a qualitative analysis of the nodule and inclusions in the steel, identifies improvement measures, and achieves good results.

Statistics on steel grades with clogging

Handan Iron and Steel Group’s Handan Baosteel Plant has experienced multiple instances of sprue detachment after sprue nodule formation during continuous casting, causing casting difficulties, severe slab grinding, and surface defects in the final products. Sprue nodule detachment primarily occurs in low-carbon mild steel products, is more common in ultra-low-carbon automotive steel products, and is relatively less frequent in high-strength steels . The steel grades affected by sprue nodule formation are wide-ranging, including low-carbon steels such as SPHD , SPHC , DC03 , DC04 , DX56D+Z , DX54D+Z , and HX260LAD+Z , as well as medium-carbon steels like SS400 and low-alloy high-strength steels like CR340/590DP , all exhibiting varying degrees of nodule formation. The formation of nodules affects the flow pattern and flow field of molten steel within the crystallizer , influencing the floating of inclusions in the molten steel, causing fluctuations in the crystallizer surface, and impacting the internal quality of the cast billet. In particular, when nodules are washed away by the molten steel and fall into the solidified billet, they form significant inclusions and scale defects. During the next hot rolling process, various shapes such as long strips and palm shapes, and even scale defects that penetrate the upper and lower surfaces, appear on the surface of the strip, severely affecting the surface quality and performance of the hot-rolled strip. As hot-rolled commercial coils, they may develop forming cracks and breakages during use; as cold-rolled raw material, they may cause strip breakage during pickling .

Four typical defects in submersible nozzles

Type I scarring defects caused by sub entry nozzle clogging

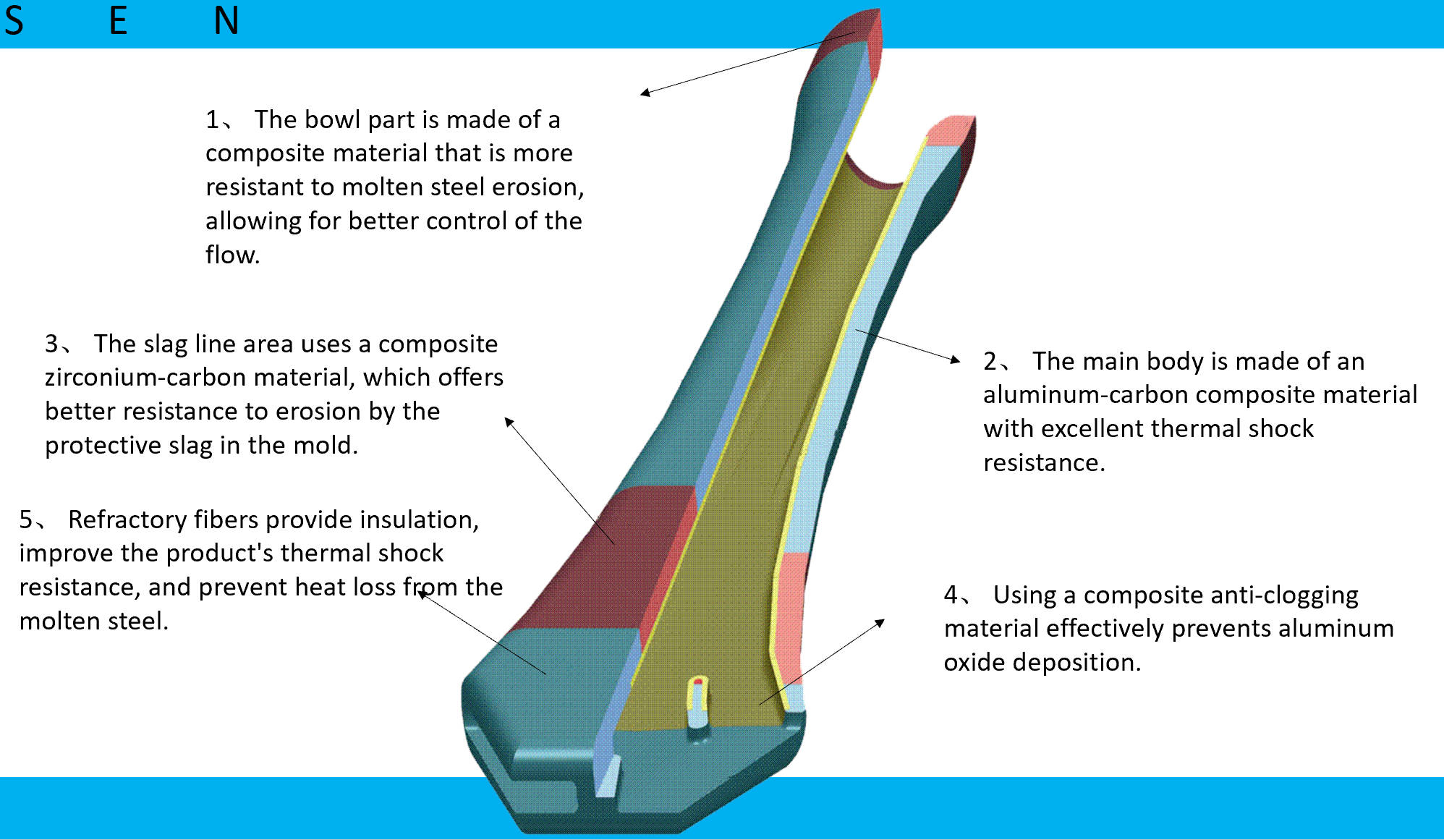

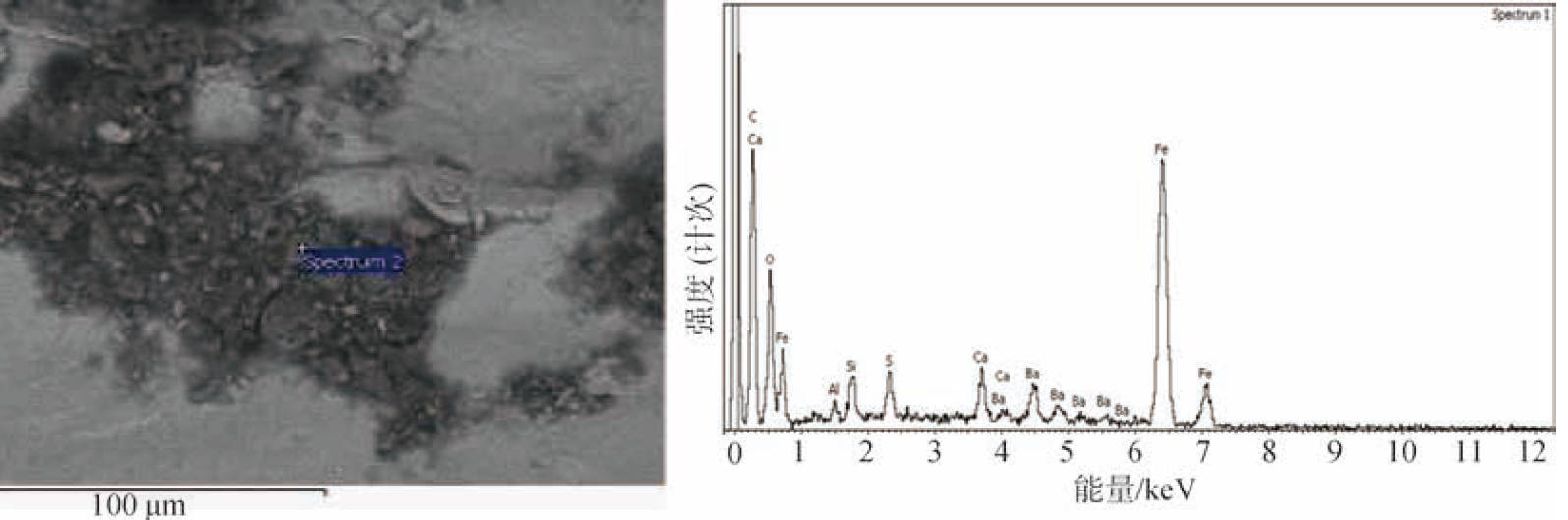

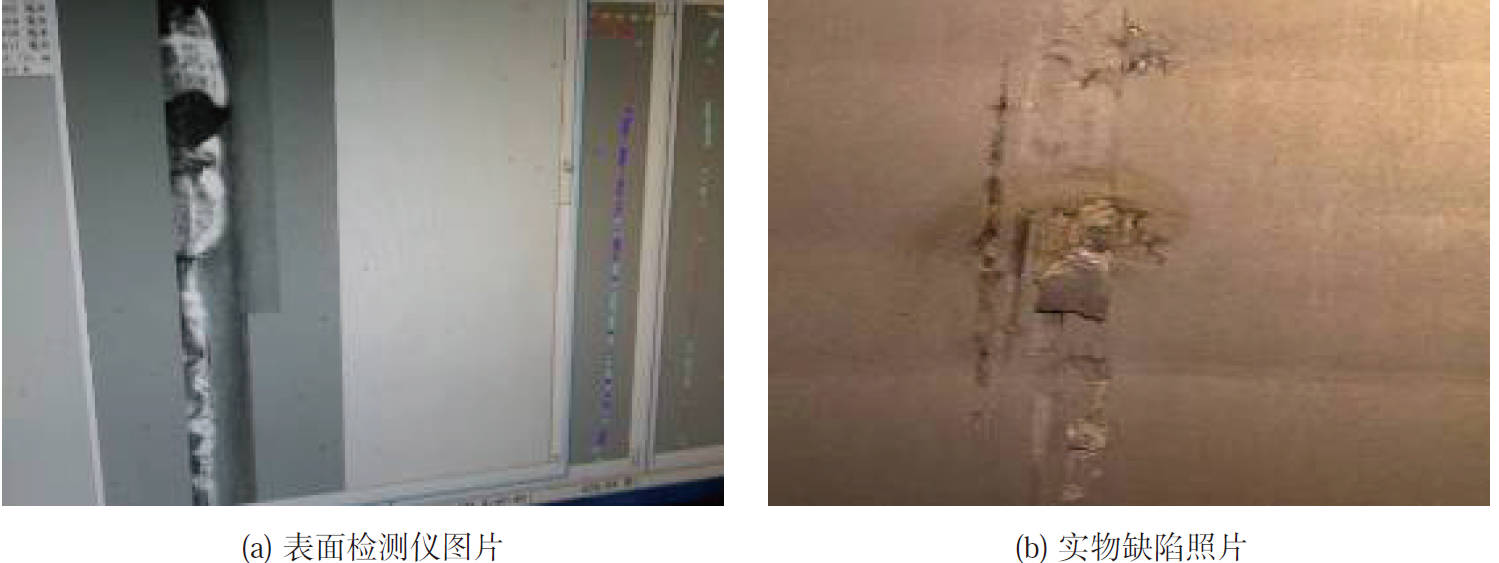

Figure 2(a) shows the scale defect detected by the surface quality inspector of the hot rolling mill.

It can be seen that some areas of this type of defect exhibit large-area defects with different shades of gray, such as black, gray, and bright white. This indicates that the defects are uneven, with protrusions and depressions, and the shape of the defects is irregular , possibly along the rolling direction or perpendicular to the rolling direction. From the actual object in Figure 2(b) , large cracks and pits appear at the defect location, and they are fragmented. The energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) image of the first type of scale defect is shown in Figure 3. From the electron microscopy results, the defect location contains Ca , S , Ba , Al , Si , and O elements. Ba originates from the steelmaking process ( submerged entry nozzle debris or steel slag ) , while Ca , Al , Si , and O elements originate from impurities brought by protective slag or steel slag. Currently, this type of defect is defined as: the first type of scale defect caused by submerged entry nozzle clogging.

Type II scarring defects caused by immersion nozzle clogging

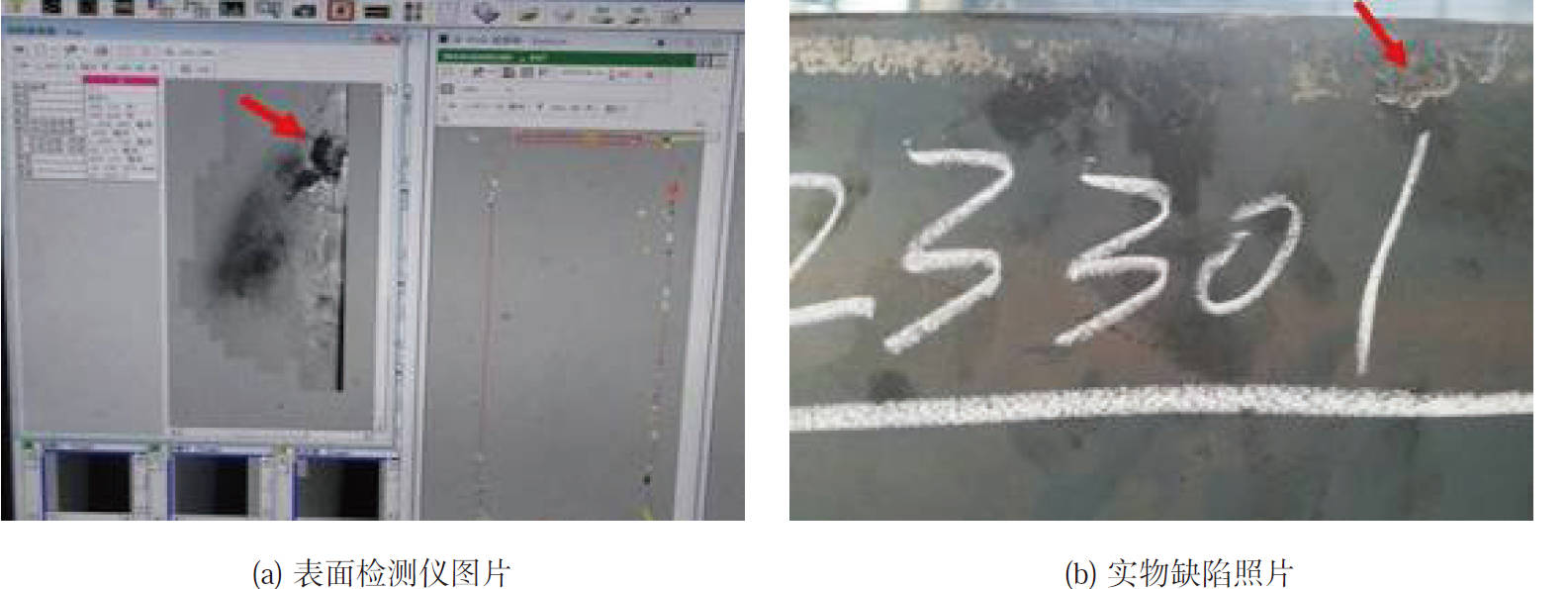

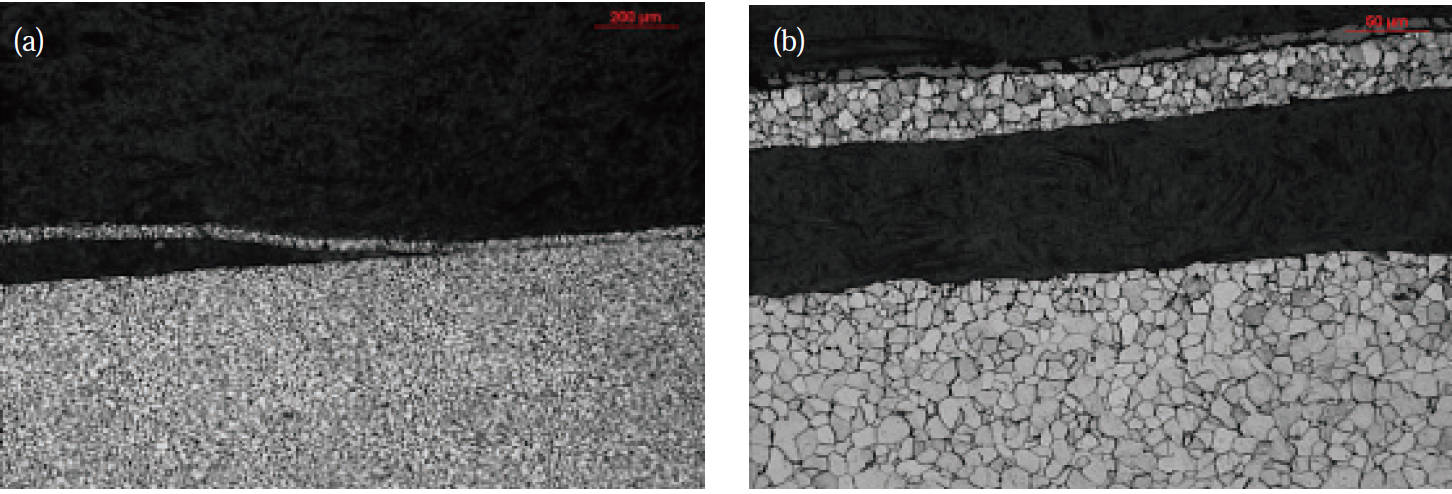

As shown in Figure 4(a),

this type of defect presents as large blocks of varying gray tones, often appearing on the upper surface of the strip, distributed at the head, middle, and tail of the strip. A dark depression exists in the center of the bright white band , with a certain length and width. Figure 4(b) shows a slight raised area at the defect location, with a relatively long and varying width, exhibiting a bright white stripe with a metallic luster. This type of defect is a typical edge scar defect. The normal matrix structure consists of ferrite and a small amount of pearlite. The defect location contains abnormal structure, along with a small amount of matrix structure, indicating that the foreign material at the defect location has fused with the matrix. The metallographic photograph is shown in Figure 5 .

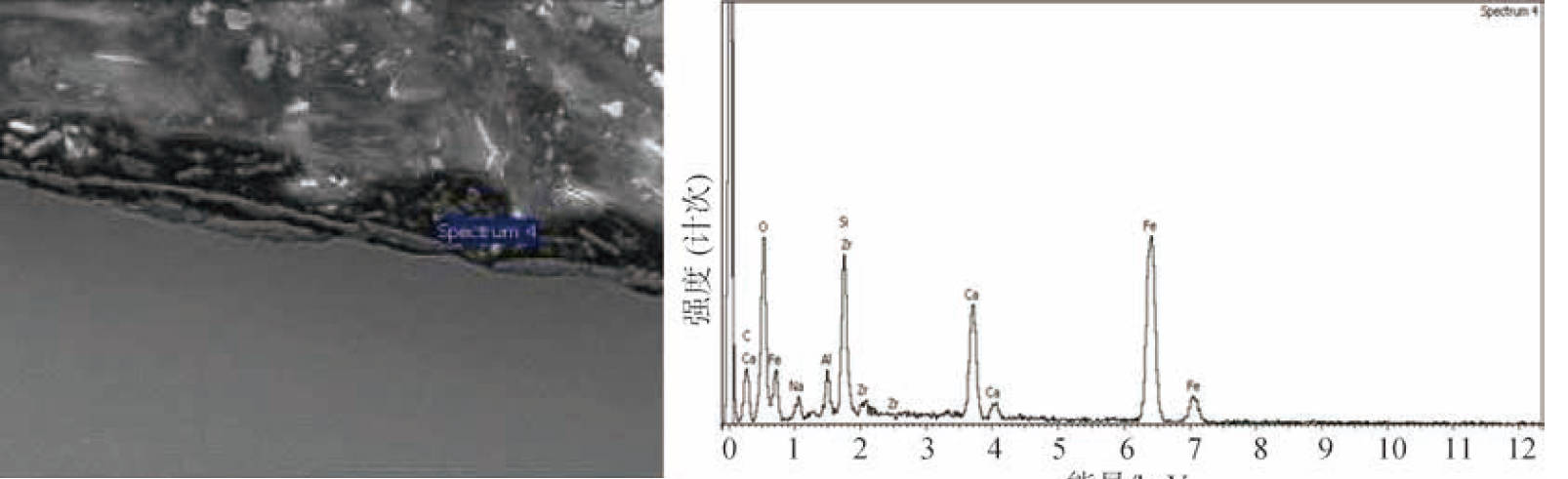

The energy dispersive spectroscopy ( EDS ) image of the second type of scaling defect is shown in Figure 6.

The electron microscopy results indicate that the defect location contains elements such as Ca , Na , S , and Ba . Ca may originate from refining slag or protective slag, while Ba originates from the steelmaking process ( submerged entry nozzle debris or steel slag ) . In the smelting of this type of ordinary low-carbon steel, an aluminum-carbon submerged entry nozzle is used in the crystallizer. The slag line portion of the outer layer of the nozzle in contact with the protective slag contains Ba . Ba originates from the submerged entry nozzle nodules reaching a certain extent, which, along with other impurities such as Al , Mg , O , and Ca , detach and fall into the molten steel in the crystallizer, forming this type of defect after continuous casting and rolling. Currently, this type of defect is defined as: the second type of scaling defect caused by submerged entry nozzle nodules.

Type III surface scaling defects caused by partial detachment of sub entry nozzles

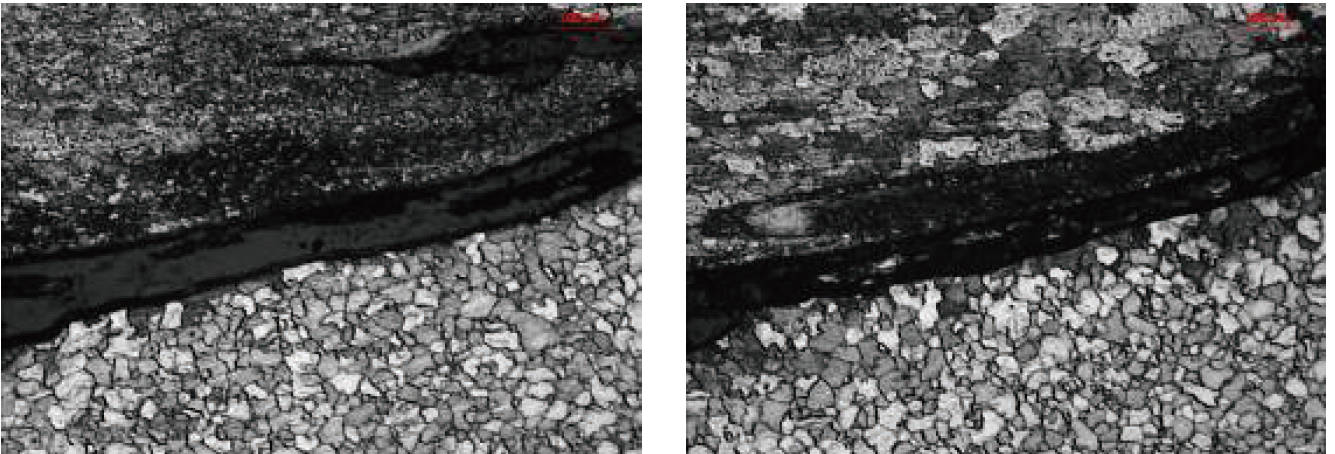

The surface quality inspection image shows that the defect extends long along the rolling direction, presenting as irregular bright and dark stripes of varying grayscale, as shown in Figure 7(a) .

Macroscopic photographs show that the defect area presents as a thin, skin-like protrusion, with some of the protrusions already cracked. The defect is strip-shaped, 2–7 mm wide , with the longest reaching 5 m . A typical metallographic image of a third-type surface scar defect is shown in Figure 8.

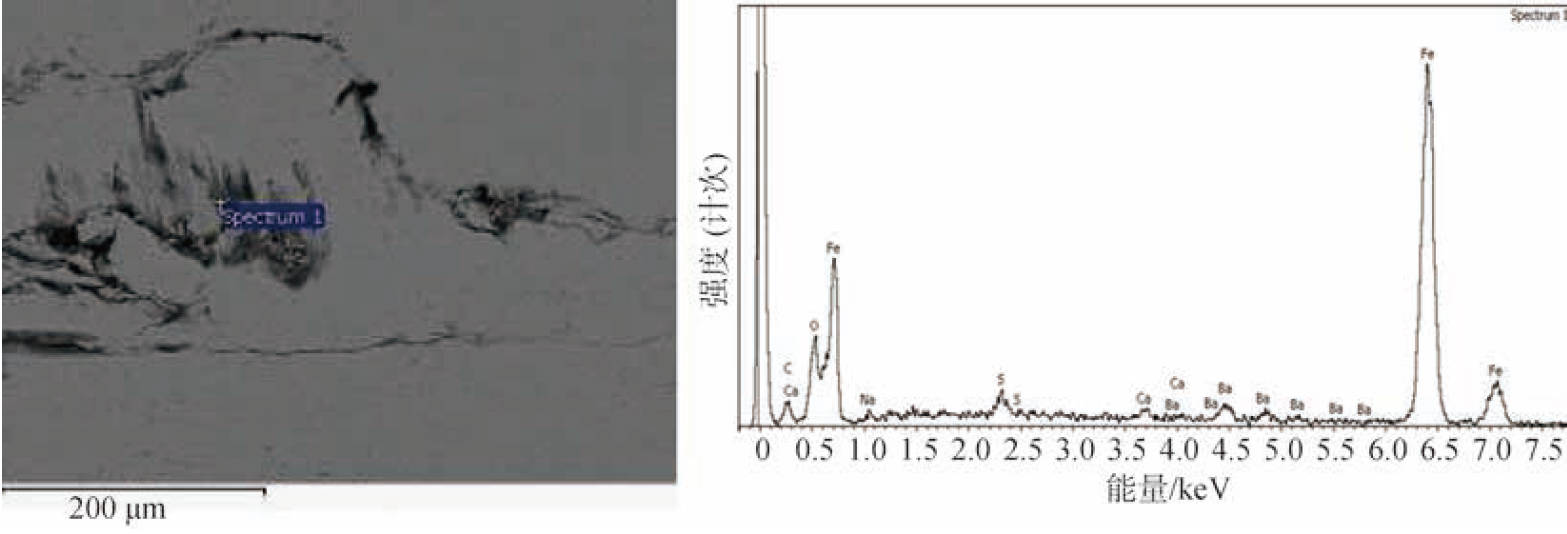

Metallographic image 8(b) shows that the maximum separation of the thin, skin-like protrusion from the substrate reaches 110 mm . Due to the large number and thinness of the protrusions, the defect can be manually removed during sampling and sample processing. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis is shown in Figure 9.

First, a spherical location with rhomboid edges was selected for EDS analysis. The results showed that this location contained Zr , Al , Ca , and Na elements, with Zr showing a peak content of 32.18% . The remainder consisted of Fe and O elements. In the smelting of this type of ordinary low-carbon steel, an aluminum-carbon submerged entry nozzle is used in the crystallizer. The slag line portion of the nozzle’s outer layer in contact with the protective slag contains Zr . Currently, this type of defect is defined as a third type of surface scaling defect introduced by localized detachment of the submerged entry nozzle.

Type IV inclusion defects caused by nodule formation in submerged nozzles

These types of defects mostly appear on the upper surface of the strip steel. As shown in Figure 10(a) by the surface inspection instrument,

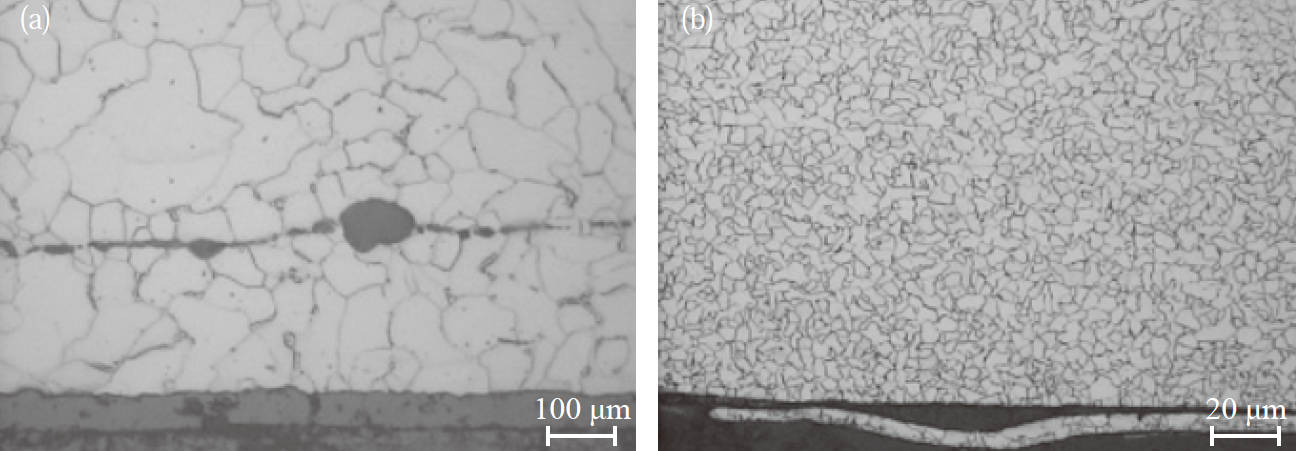

they are elongated and relatively wide, distributed in multiple locations along the length and width of the strip steel. In strip steel with this type of defect, large areas of white powdery material are present at the defect location. This material is relatively hard and brittle, and easily detaches under external force. The microstructure detection results of this type of defect are shown in Figure 11.

The surface also shows warping, and there is a long intergranular crack at the crack root . When magnified 500 times, the warped area along the grain boundary crack contains inclusions, as shown in Figure 11(b) . The energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) image of the crack location is shown in Figure 12.

It can be seen that the defect location contains elements such as Zr , Al , Mg , O , and Ca , with Zr and Al showing certain peak values. Al originates from the LF refining deoxidation process; Mg may originate from the converter, refining, or refractory materials; and Ca may originate from refining slag or protective slag. When smelting this type of ordinary low-carbon steel, an aluminum-carbon submerged entry nozzle is used in the crystallizer. The slag line area where the outer layer of the nozzle contacts the protective slag contains Zr . Zr originates from the process where, after the submerged entry nozzle agglomerates to a certain extent, other impurities such as Al , Mg , O , and Ca detach and fall into the molten steel in the crystallizer. This defect forms after continuous casting and rolling. Currently, this type of defect is defined as the fourth type of inclusion defect caused by submerged entry nozzle agglomeration.

Analysis of the source and mechanism of clogging formation

Mechanism of clogging formation in sub entry nozzles

The submerged entry nozzle, located between the tundish and the crystallizer, primarily serves to transport molten steel, isolate it from air to prevent secondary oxidation, and promote the flotation of inclusions. When high-temperature molten steel flows through the submerged entry nozzle, the coating layer on the inner wall is quickly washed away, exposing carbon (C ) in the refractory material. At the casting temperature (1500~1550 ℃ ) , C is easily oxidized, forming a rough, dark brown decarburized layer approximately 0.5~1.0 mm thick, providing a favorable environment for inclusion adhesion. Due to the boundary layer, the flow velocity of the molten steel near the nozzle wall is almost zero when it flows through the nozzle , making it easy for high-melting-point inclusions in the molten steel to adhere to the nozzle wall. Studies have shown that the wetting angle between high-interfacial-energy alumina and molten steel is 140° . The interfacial tension between molten steel and alumina is relatively high, making them highly prone to adhesion to the inner wall of the nozzle. Some literature indicates that the adhesion time between two 10 μm alumina inclusions is only 0.031 s . Furthermore, the turbulence that occurs during the flow of molten steel significantly increases the probability of collisions between high-temperature inclusions, accelerating the formation of nozzle clogging.

Main components of sub entry nozzle clogging

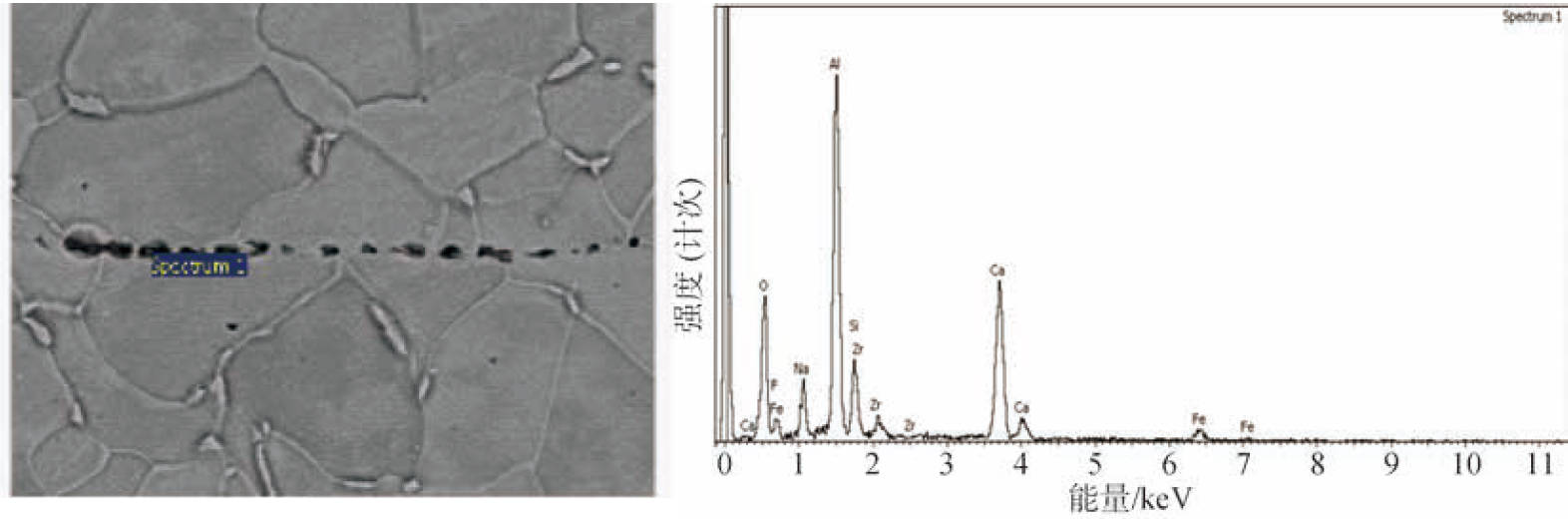

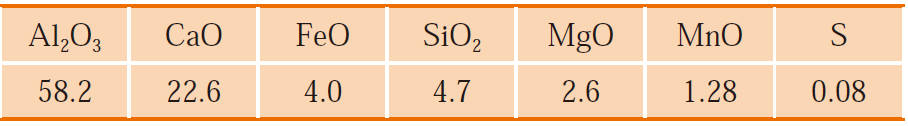

After casting, the submerged entry nozzle was dissected and found to contain numerous cauliflower-shaped nodules adhering to the inner wall of the nozzle. The nodules were approximately 9 mm thick, grayish-white in color, and relatively dense on the side adhering to the nozzle wall, while looser on the side closer to the molten steel . Samples of the nodules were analyzed, and their composition is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 shows that the nodules were mainly composed of Al₂O₃ . Microscopic analysis of the nodules using scanning electron microscopy revealed that the main phases included a large amount of oxides and diffusely distributed steel particles. Analysis using the energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analyzer on the EMS revealed that the main elements were Al , Ca , and O. Based on the elemental ratios , the main components of the nodules were Al₂O₃ , CaO ·Al₂O₃ , or CaO· 2Al₂O₃ . Mg and a small amount of Zr were also found in the field of view near the nozzle wall , with the Zr likely introduced by the nozzle material itself . The presence of O and Al elements around Mg indicates that Al₂O₃ – MnO -MgO composite inclusions should also exist in the nodule . Si and S elements were also found in the view, with S mainly distributed on the side closer to the molten steel, indicating that Al₂O₃ – CaO – SiO₂ composite inclusions and calcium sulfide inclusions also exist in the nodule.

Sources of nodule formation in sub entry nozzles

Since most of the steel grades that develop nodules are low-carbon aluminum deoxidized killed steel, the test results show that the nodules are mainly alumina inclusions. Through analysis of the molten steel composition and the refining slag, it was found that the alumina mainly comes from the following sources:

(1) Statistical analysis of the composition of low-carbon aluminum-killed steel (SPHD) molten steel revealed that the w (Al <sub>s</sub> )/ w (Al<sub> t</sub> ) ratio in the molten steel was only between 18.2% and 21.5% , indicating a low proportion of acid-fused aluminum and a high content of alumina, suggesting insufficient removal of alumina from the steel. The alumina suspended in the molten steel adhered to the inner wall of the submerged entry nozzle, forming nodules when flowing through it.

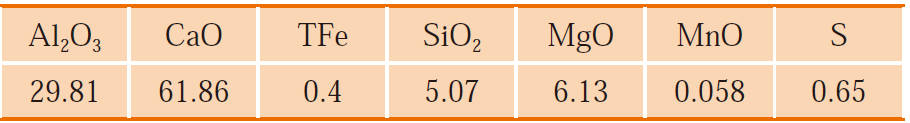

(2) The composition of the refining slag was obtained by sampling and testing .

Table 2 shows that the MnO content in the refining slag was only 0.058% , while the MnO content detected in the nodules on the inner wall of the nozzle was all above 1.0% . Based on the changes in the composition of manganese oxide, it can be seen that there was secondary oxidation in the molten steel, indicating that some of the aluminum oxide inclusions in the nodules came from the secondary oxidation of the molten steel.

(3) SiO2 , MnO , and FeO in refractory materials or slag react with free Al in steel to form Al2O3 inclusions that adhere to the inner wall of the nozzle. In addition, the temperature of the molten steel will drop during the casting process, causing a shift in chemical equilibrium. Oxygen will be released from the steel, and the released oxygen will react with free aluminum in the steel to form aluminum oxide inclusions.

(4) Since the low-carbon aluminum-killed steel produced by Handan Baosteel Plant all employs calcium treatment technology, studies have shown that when calcium is used to treat molten steel, calcium first changes the oxide properties, initially forming CaO·2Al2O3 . As the activity of calcium increases, it then forms CaO·Al2O3 , eventually resulting in low-melting-point 12CaO·7Al2O3 inclusions. However, when the calcium-to-aluminum ratio in the molten steel is too low, only high-melting-point CaO·2Al2O3 or CaO·Al2O3 will form in the steel. The concentration of Al , Ca , and O elements found in the nozzle nodules also illustrates this point. Furthermore, if there is too much sulfur in the steel during calcium treatment , Ca will first react with the sulfur in the steel to form high-melting-point CaS , causing nozzle nodules.

Measures to prevent nodule formation in Sub entry nozzles

Steel tapping process control

The converter adopts a sliding plate slag-blocking technology to strictly control the leakage of high- FeO slag from the converter into the ladle, so that the slag thickness in the ladle is controlled at about 60 mm . In addition, 200 kg of fine lime is added to the ladle before tapping , and 150 kg of slag conditioner containing about 25% Al is added after tapping to reduce the oxidizing properties of the steel slag.

Refining process control

(1) For low-carbon steel with severe nodule formation, the original one-time aluminum wire feeding method at the time of leaving the station has been changed to the current two-time aluminum wire feeding method to facilitate the removal of aluminum trioxide in the steel.

(2) Optimize the calcium treatment process and increase the calcium-aluminum ratio . Through multiple tracking experiments, it was found that when the calcium-aluminum ratio in the steel is increased to 0.13 , the phenomenon of nozzle nodule formation is less likely to occur.

(3) Reasonably control the argon blowing intensity and appropriately extend the argon blowing time to ensure that the argon blowing time is not less than 7 min after refining .

Secondary oxidation control in continuous casting

(1) Improve the automatic pouring rate of the ladle and reduce the number of times the ladle is burned . Add a sealing gasket at the connection between the sliding nozzle and the long nozzle, and perform argon blowing to prevent oxygen absorption due to negative pressure during the downward flow of molten steel. Use a ladle slag detection device to reduce slag discharge from the ladle.

(2) Argon is blown into the tundish before casting , the liquid level in the tundish is stabilized during the casting process, the exposed molten steel is prevented, and the submerged nozzle is sealed with argon to prevent oxygen from being absorbed by the submerged nozzle.

(3) Argon blowing with a stopper rod can blow away a small amount of adhesion from the immersion nozzle, slowing down the growth rate of nodules.

Appropriate selection of nozzle material

When casting aluminum-killed steel, using fused silica nozzles reduces glass viscosity by generating a glass layer rich in SiO2 , which can reduce nozzle clogging to some extent. When casting high-manganese steel, wrapping the aluminum-carbon nozzle with a layer of refractory material for insulation helps prevent clogging. Zirconium and quartz nozzles should be used for casting plain carbon steel and low-alloy steel. Graphite high-alumina nozzles should be used for casting aluminum-containing steel grades or steel grades with a manganese content higher than 0.65% .